(CNN) — Open a newspaper on any given day here in this small Europe nation known for high taxes, generous government services and its stubbornly happy citizens, and you’ll almost certainly find a story about the U.S. presidential election.

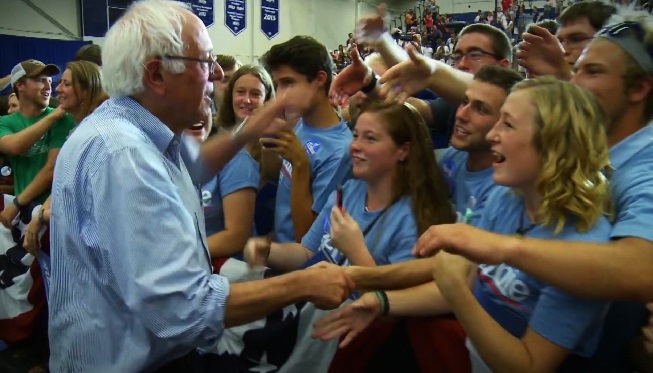

The Danes are following the race with an astounding level of enthusiasm and interest in part because Bernie Sanders, one of the leading candidates for the Democratic nomination, won’t stop talking about them.

Sanders has proudly adopted the label of a “democratic socialist,” and he has pointed to Denmark as a model for his vision of an ideal American future.

At a presidential debate hosted by CNN in October, Sanders brought up Denmark and the surrounding Scandinavian states when asked to describe what “democratic socialism” means to him.

“I think we should look to countries like Denmark, like Sweden and Norway,” Sanders said, “and learn what they have accomplished for their working people.”

“We are not Denmark,” Hillary Clinton responded.

The senator’s affinity for the Danish society has stretched back years. In 2013, after hosting the Danish Prime Minister on a tour of his home state of Vermont, Sanders wrote an essay praising their model of government.

“In Denmark, there is a very different understanding of what ‘freedom’ means,” Sanders wrote, arguing the U.S. could learn from the way the Danes have “gone a long way to ending the enormous anxieties that comes with economic insecurity.”

“Instead of promoting a system which allows a few to have enormous wealth, they have developed a system which guarantees a strong minimal standard of living to all — including the children, the elderly and the disabled,” Sanders added.

While the Danes are flattered by all the attention, they want to ensure that the love coming from Sanders doesn’t confuse people into thinking they describe themselves “socialists,” too. Sanders has clarified that his democratic socialism is not the same as “socialist” in the traditional sense of a purely government-controlled economy. But that hasn’t stopped Danish leaders from ensuring there is no misconception about their own system.

“I would like to make one thing clear,” Danish Prime Minister Lars Lokke Rasmussen said recently in a speech at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “Denmark is far from a socialist planned economy. Denmark is a market economy.”

But it is a market with many differences from the United States. All Danish citizens have access to child care, state-guaranteed medical and parental leave from work, free college tuition in which students receive a paycheck from the government during enrollment, free health care and a generous pension, all of which Sanders supports.

“Free” is actually the wrong word to describe these services. Danes pay some of the highest taxes in the world, including a 25% tax on all goods and services, a top marginal tax rate hovering near 60%. The top tax rate in the U.S., by comparison, is less than 40%.

But there are aspects to the Danish model that you would never see on Sanders’ policy platform. As a small country heavily reliant on trade, Denmark imposes minimal tariffs on foreign goods. Businesses here are only lightly regulated. The corporate tax rate is much lower than in the United States, which has one of the highest in the world. There’s not even a minimum wage in Denmark, although most workers are paid high salaries in large part due to the strength of labor unions. And in the past few years, Danish voters elected a right-of-center government, which has been instituting reforms that have put tighter restrictions on access to the long-held safety net.

The recent changes have caught the attention of conservative and libertarian think tanks in North America that rank levels of economic freedom around the world. Over the past few years, studies conducted by the Heritage Foundation, Wall Street Journal, the Cato Institute and the Canadian Fraser Institute have ranked Denmark as having actually more economic freedom than the United States.

“There is this idea that we are a heavily regulated society with a closed economy. The opposite is true,” said Bo Lidegaard, the executive editor-in-chief of Politiken, one of Denmark’s leading newspapers. “If by socialist you mean regulated, restrictive, the individual is not free to do what she or he wants, that is not what we have here. We have a society where the individual is perhaps freer than any other society because the government is securing the social contract so comprehensively.”

In terms of pure semantics, few Danish politicians today would characterize themselves as “socialist”–even a “democratic socialist”–as Sanders does. The word has largely fallen out of fashion in recent decades.

“When I hear Bernie Sanders talk about himself as a democratic socialist, it’s a little bit 1970s,” said Lars Christensen, a Danish economist known here as an outspoken critic of his homeland’s model. “The major political parties on the center-left and the center-right would oppose many of the proposals of Bernie Sanders on the regulatory side as being too leftist.”

Could the U.S. adopt the Danish model?

As even Sanders has conceded, the differences between the United States and Denmark are striking. In many ways, Denmark’s success depends on its small size. The country has a population of just 5.6 million — about the same as Minnesota’s — and its territory makes up just 16,000 square miles, about half the size of South Carolina. By comparison, the United States has a population of more than 300 million and encompasses 3.8 million square miles.

Unlike the United States’ diverse population of immigrants, Denmark is ethnically homogenous — nearly 90% are of Danish ancestry, according to The Danish Ministry of Social Affairs and Integration — making political consensus easier than in the United States.

“I think this system is only possible because we essentially are all the same,” said Christensen. “Maybe if you wanted to introduce such a scheme in Utah, you could do that. But doing it across the U.S., I find it completely and utterly impossible just for the mere fact that Americans are all so different.”

Danish citizens also seem to have a higher comfort level and trust in government than in the United States. One would be hard-pressed to find a mainstream Danish politician who would agree with Ronald Reagan’s axiom that, “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are, ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.”

While Americans have a deep-seated distrust of government that was imprinted on the nation’s soul in the Bill of Rights, the Danish just don’t view their government’s size as a recipe for tyranny.

“The question is not how much tax you pay or how big your government is, it’s whether it works,” Lidegaard said. “It’s whether you get return on your payment. We pay a lot of taxes, but we get a lot in return.”

The Danish also participate in the democratic process on a scale unheard of in the United States. More than 85% of Danish citizens participated in the nation’s general election in 2015; Only 55% of Americans went to the polls in 2012.

A system challenged by a changing world

Sanders would also probably have concerns with the way Denmark has handled the European migrant crisis.

While Denmark is accustomed to international media’s fawning over its safety net and consistent ranking by research organizations as having the happiest citizens in the world, the government has come under severe criticism for how it has handled the recent wave of immigrants coming from the war-torn Middle East.

Fearful that the thousands of refugees pouring in the European Union from Iraq and Syria could threaten their society, the Danish government has gone to great — and controversial — lengths to dissuade migrants from settling in their country.

The most problematic move came when the government passed a law that would grant the state the right to seize possessions worth more than the equivalent of about $1,500 from refugees settling in Denmark who seek aid from the government. The law includes a carve-out for items of “special sentimental value,” but the critical reaction from human rights groups was swift and punishing.

The law also increases the number of years refugees would have to wait to bring family members into the country and it made it more difficult for them to obtain permanent residency. Its passage comes amid the rise of the right-wing Danish People’s Party, which has made combating immigration a chief priority.

“There is an inherent contradiction between a welfare state where all your life you pay taxes to have coverage — health, social costs, etc. — and then being in the country as a migrant only part of your life,” said Lidegaard. “The problem with the law — and there is one — is that it’s trying to send a signal: Immigrants in Europe, don’t go here. Don’t come to Denmark. The signal sent that way is a stupid signal to send. That’s the purpose of the law. It’s not a practical measure.”

Before the law passed, Denmark’s Ministry of Immigration, Integration and Housing published ads in Arab and English-language newspapers in Lebanon, where more than 1 million Syrian refugees live, warning immigrants that Denmark will be an unwelcoming place for them.

The fear, generally, is that the foreign culture brought by the refugees would not align with traditional Danish customs and disrupt the recipe for what makes the welfare state possible.

“There is a limit to how many immigrants we can take in from a different culture who don’t speak the language and how fast we can turn them into becoming citizens that are part of society, that are able to function and contribute to the wealth of our society,” said Lidegaard.”So we have a lot of focus now on how we integrate newcomers. How we turn immigrants into citizens who are part of production, part of taxpaying, part of paying the bill.”

The Danes are watching us

Even though Danes are eager participants in their own elections, the amount of time they spend watching and discussing our elections is a phenomenon to behold.

“American politics is really, really popular in Denmark,” said Anders Agner Pedersen, a Danish journalist who edits Kongressen, a news outlet that exclusively American politics for a Danish audience. “It basically is in the news every day.”

Pedersen, who has to stay up all night to watch American presidential debates and state primary returns from Denmark, is swamped with bookings on Danish television and radio programs to explain the election process and analyze the daily horse race. He recently hosted what he thought would be a small salon session to discuss the primaries at a Copenhagen restaurant and was shocked when more than 100 Danes showed up to get their American political fix.

“You guys do quite a good show,” he said of the American election process.

Sanders isn’t the only candidate the Danes are talking about. Donald Trump is a source of constant fascination — and perhaps even a little terror — in the Nordic region. In January, when three young children who call themselves the “USA Freedom Kids” dressed up in red, white and blue and performed a song-and-dance number about Trump at one of his rallies in Florida, the video skyrocketed throughout Danish social media.

And just this month, Ted Cruz set Danish media aflame when he suggested that Donald Trump was so unhinged he’s liable to drop an atom bomb on Denmark. The Danes were bewildered: Why us?

As the campaign marches on with Trump still riding high in the polls, his ongoing success is starting to become a concern here.

“In the beginning I thought it was a joke. Then we realized people were voting for Trump,” Jonas Pedersen, a medical student at the University of Copenhagen, said.

Another medical student, Helena Boegh, said, “That some people would actually vote for Donald Trump and in the same country would vote for someone who likes the system we have in Denmark — that really says something about America.”

The-CNN-Wire ™ & © 2016 Cable News Network, Inc., a Time Warner Company. All rights reserved. (Photo: CNN)